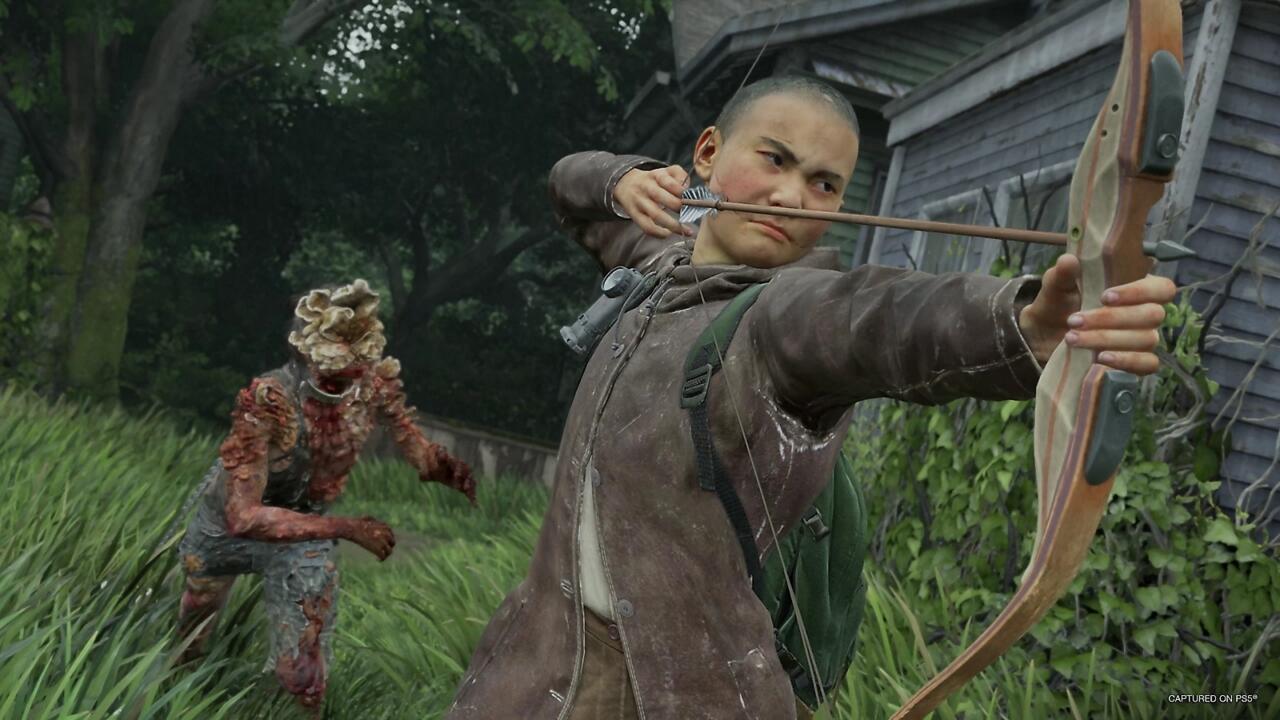

Combat in

But the issue is less that adding the No Return mode was a bad decision and more the fact that making a triple-A action video game is a fraught endeavor, and one that might not be able to handle conveying the sort of ideas that The Last of Us Part 2 trades in. This was also the case in the original release, in fact, as well as in the first game. This is a series that wants to raise big questions about the stain violence leaves on the soul, about the indirect harm it’s possible to do to people, about the cycles of pain and ruination that people can bring on others and themselves. But you still murder, like, hundreds of people by the end. The primary interactive thrust, the thing that you do in these games, is kill people.

These games are entertaining, the conflict and triumph are exciting, and the mechanics are specifically designed to maximize those emotions. In other words, Naughty Dog might want you to think “violence is bad,” but they still did all they could to make violence fun as hell. No Return just distills that dissonance without the moralizing that The Last of Us Part 2 often does poorly throughout its campaign.

At the same time, No Return is fun, but it’s not that fun, because the brainier elements of The Last of Us Part 2 are always getting in its way. Without the reason for the realism, the realism becomes an anchor holding back what makes the combat entertaining. The slow executions are annoyingly slow. The clunky fights feel like purposeful handicaps at odds with your ability to skillfully master the mechanics. Dropping into encounters where the enemies are already on alert becomes less exciting than frustrating as you get cut apart by enemies charging you with little regard for their own lives. It all becomes video gamey, but not in a way that’s satisfying.

It reminds me of the moment that really turned me against Spec Ops: The Line, a game that famously makes a point about video game violence. At some point, you have the opportunity to use white phosphorus–a war crime–against a group of enemies. It’s obvious that this is bad from the get-go, and yet you’re left with no other options; you can’t progress without using the white phosphorus. Five seconds later, sure enough, you walk through the battlefield and see that you murdered not soldiers but civilians, although either case would be equally horrific. The game then chastises you for your decision, as if you could have made any other one but turning the game off.

That moment always bothered me for a few reasons. First, Spec Ops: The Line wanted me to feel bad for making a decision it forced on me; second, developer Yager Development seemed to have no qualms about taking my money to make this violent interactive experience; and third, the game had a multiplayer mode. Making a comment on video game violence was completely undermined by also selling the fun of shooting both computer-controlled soldiers and other players.

And with No Return, that feels like the case of The Last of Us Part 2, as well. It doesn’t seem possible for Naughty Dog to make a game that accomplishes these gameplay goals and these story goals. It’s not just that there’s the dreaded ludonarrative dissonance at play here–it’s that the game is struggling to combine concepts of fun and meaning in a thoughtful way, and can’t really manage it.

I liked No Return because I liked the combat mechanics of The Last of Us Part 2, but it doesn’t really have all that much to offer. After a few hours of different combinations of elements and random character traits, it feels like I’ve gotten everything I can out of it, and it never really becomes compelling enough to make me want to keep playing it like I might other action games or roguelikes. These are game mechanics that try to serve too many goals at once, and in the end, can’t serve any very well.